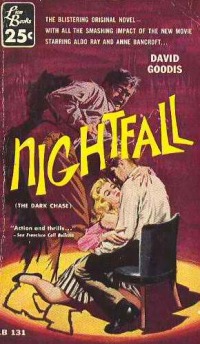

Nightfall by David Goodis

Sunday, January 13, 2013 at 8:50AM

Sunday, January 13, 2013 at 8:50AM

First published in 1947

Vanning is hiding out in Greenwich Village. He doesn't know Fraser is watching him. Neither does he know that two men who robbed a bank in Seattle are in New York, but he knows those men are after him. They think he has the $300,000 that was stolen from the bank. Fraser thinks Vanning might be the third robber. The evidence suggests that Vanning, using the name Dilks, met with a man named Harrison, killed him, and fled with the $300,000, cash that Harrison was supposed to launder. Yet Fraser can't wrap his head around Vanning's participation in a bank robbery, much less a murder. Vanning is a commercial artist, a former naval officer with no criminal record. Fraser doesn't want to arrest Vanning until he knows he can recover the money, but his doubts about Vanning's guilt haunt him because the evidence is probably sufficient to send Vanning to the electric chair.

When the two robbers catch up with Vanning, he claims he doesn't know where the money is. Is Vanning telling the truth? In a plot worthy of a Hitchcock movie (Nightfall was filmed but not by Hitchcock), Vanning is the traditional figure who finds himself in the wrong place at the wrong time. Vanning is torn between his desire to go to the police and his certainty that the police will always follow the easy path. The evidence points to Vanning's guilt and Vanning knows that nothing he can say to the police will convince them otherwise -- especially given his inability to produce the $300,000 that he knows he once had. It's the missing money that makes Nightfall different from thrillers that follow the "innocent man trying to prove his innocence" formula.

This isn't David Goodis' most suspenseful novel, but the plot is intriguing. Nightfall is the kind of low key crime novel that modern authors, obsessed with martial arts and car chases, seem unable to replicate. The novel's thrills come from tension rather than action. Its focus is on psychology rather than gunplay. The story's violent moments are explosive but contained, usually related in a paragraph or two. Goodis tosses a love story into the mix that I thought was unconvincing, but that reaction was tempered by the knowledge that Vanning isn't capable of thinking clearly.

Goodis gives the gift of realism to his characters. Responding to the stress of an untenable situation, Vanning slowly comes unglued. He behaves foolishly and can't understand why. He feels himself being dragged down in "a whirlpool of defeat." He's disappointed in himself ("I can't get a practical thought in my head," he says), but as Fraser tells him, if we really knew ourselves, "we'd be adding machines instead of human beings." Frasier suffers from crippling self-doubt as he worries that Vanning has either escaped or been captured by the robbers. A small-minded robber with big plans is motivated by the desire to escape the crushing force of ordinary life. The female character, Vanning's love interest, is a bit thin, but the other primary characters have full personalities.

Noir is dark by definition, but Goodis filled his novels with the contrast of color. The interiors of apartments have paintings of orange sunsets over gray-green water hanging on sky blue walls. Goodis changes up his prose style, sometimes writing stark sentences, sometimes rambling. He tells the story in the first person but Vanning occasionally talks about himself in the third person, a symptom of his deteriorating mental status. Dialog is snappy. The resolution is satisfying, although perhaps too bright for a true noir tale. In short, although David Goodis wrote better books than Nightfall, the solid prose, tight plot, and insightful characterizations make Nightfall an enjoyable read.

RECOMMENDED

Reader Comments