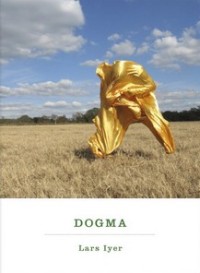

Dogma by Lars Iyer

Monday, February 27, 2012 at 4:24AM

Monday, February 27, 2012 at 4:24AM

Published by Melville House on February 21, 2012

Lars and W., two friends last seen wandering through life in Spurious, return in Dogma. The end is still near. Lars is still the butt of W's scathing criticism and the recipient of his opinions on subjects ranging from courtship to capitalism. Lars' flat is still damp. Lars and W. are still loyal to their idealistic vision of an unspoiled Canada. They are still fond of Kafka and Plymouth gin. They are still trying to understand religion and Rosenzweig. They still embrace life while feeling defeated by it, no more consequential than "leaves swept up in an autumn storm."

New in Dogma: W. images himself as Diogenes while visiting Nashville ("the Athens of the South"), while deeming Lars "a Diogenes gone mad"; Lars and W. compare the British to Americans (who can't make true distinctions, particularly when it comes to gin); Lars writes poetry of despair; W. takes Lars on a pointing tour of Plymouth (where Lars photographs W. pointing at architecture he admires).

Also new is the intellectual movement that W. and Lars decide to christen. They call it Dogma. Dogma has rules. Dogma is spartan, full of pathos, sincere, and collaborative. Ironically, W. and Lars are none of those things, making them poor standard-bearers for the movement they invent. They are, however, according to W., "the last friends of thought." It is up to them to keep thought alive. That effort is slightly hampered by a new rule: "The Dogmatist must always be drunk" because "who can bear the thoughts that must be thought?" Fortunately they think just as much, and about as clearly, when they are drunk as when they are sober, although after drinking they have trouble remembering the other rules (not that it matters, since they add new rules on a whim).

In my favorite section of Dogma, Lars and W. travel to America on a lecture tour (their lectures, unsurprisingly, are sparsely attended). As the best and (mostly) worst of America rolls past -- novelty motels, "huge crosses looming over nowhere," miniature golf courses -- I was reminded of Humbert Humbert in Lolita. W. is as acerbic as Humbert but funnier; his commentary provokes chuckles and occasional belly laughs ("They've made a Disneyland of Armageddon!").

When a sequel is more of the same, a reader probably shouldn't complain if it is a sequel to something wonderful. Dogma gives us more of the same biting humor, more of the same maddening characters, more of the same nutrition for our minds. Still, one of the things I loved about Spurious was the sense that I'd never read anything like it. That magical feeling was missing while reading Dogma, because I've read something exactly like it: Spurious. And that, really, is one of my only two complaints about Dogma: the feeling that I was reading outtakes from Spurious. The second is that Dogma has more philosopher in-jokes than Spurious (at least I think they're in-jokes; not being a philosopher I can't pretend to understand them). I think Spurious is a bit more accessible to those of us who aren't intimately acquainted with the history of philosophy.

Those mild criticisms aside, Dogma is just as funny and provocative and stimulating as Spurious. These books are as much about friendship as anything else, and reading Dogma is like visiting old friends (albeit the kind of friends you want to keep at a distance lest they begin to annoy). I'll therefore look forward to the third book of Lars Iyer's trilogy, but with the hope that Iyer finds a way to differentiate it from the first two.

RECOMMENDED

Reader Comments