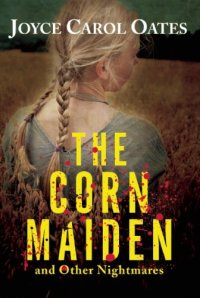

The Corn Maiden by Joyce Carol Oates

Monday, October 31, 2011 at 10:54AM

Monday, October 31, 2011 at 10:54AM

Published by Mysterious Press on November 1, 2011

Joyce Carol Oates' latest collection of stories isn't for the faint-heated. The title story -- about a girl who doesn't come home from school -- focuses less on the horror that the girl will experience than on the guilt her working class mother feels at leaving her eleven-year-old daughter home alone until she returns from the late shift she's forced to work. Guilt gives way to fear: What kind of problems will she cause for herself if she calls 911? What judgments will she face? What will the police think about the beer she's drinking to calm her nerves as she considers where her daughter might have gone? Oates uses the chilling circumstances to explore diverse sources of terror: the twisted child responsible for the missing girl's fate; the police officers who accuse and intimidate the innocent; journalists who are willing to report innuendo in their lust for a sensational story; therapists who insist that it is healthy to dredge up memories best left dormant. This is a powerful, sometimes touching, incredibly intense piece of writing. It is the longest and best of the seven stories in the collection.

My second favorite story, "Helping Hands," tells of a new widow who, in desperate loneliness, takes up with a wounded veteran. Envisioning herself as his savior and him as her protective companion, she invests him with qualities of sensitivity and intelligence that he clearly lacks, while remaining willfully blind to the man's dangerous instability.

The other "nightmares" in the collection are: "Beersheba," about a man who is forced to confront his long-forgotten failings as a stepfather; "Nobody Knows My Name," in which a young girl's natural jealousy of her newborn sister may or may not be responsible for a tragic ending; "Fossil-Figures," about a demon brother's dominance, from their days in the womb to the end of their lives, over his frail twin; "Death-Cup," another story of mismatched brothers, one of whom contemplates poisoning the other with deadly mushrooms; and "A Hole in the Head," in which a doctor revives the practice of trepanation -- drilling holes in the skull to release evil spirits.

Oates tells her stories in lush, rhythmic sentences. She sketches characters with deft precision. She fills their mouths with strong dialog, spoken in unique and realistic speech patterns. Each story builds a sense of dread, bit by bit, often indirectly -- when a mean gray cat starts stalking through the story, you know something awful is going to happen. Yet these aren't simple, predictable stories of horror or suspense. In the two stories about brothers, the characters behave surprisingly; they reveal an unexpected capacity for late-life change. Most of the stories reveal their own little surprises; all of them deliver electric jolts of anxiety before they end.

RECOMMENDED

Reader Comments