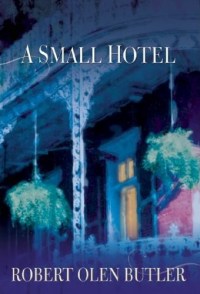

A Small Hotel by Robert Olen Butler

Saturday, July 16, 2011 at 11:32AM

Saturday, July 16, 2011 at 11:32AM

Published by Grove Press on August 6, 2011

On the day their divorce hearing is scheduled, Kelly Hays flees to a boutique hotel in the French Quarter of New Orleans while Michael Hays drives west of the city to a plantation called Oak Alley. Kelly brings bottles of Macallan and Percocet with her: an ominous combination of traveling companions. Michael brings Laurie Pruitt, the younger woman he has started seeing. Both destinations trigger memories; more than once, Kelly and Michael stayed together at the same small hotel (including the day they met) and at the plantation (where they got married).

Kelly passes her time in and near the hotel by telling herself a silent story, beginning with a flashback to the Mardis Gras celebration where she first met (and was rescued by) Michael. She reflects upon "how abiding and deep an early impression we can draw of another person from a single, unexamined incident." Eventually that story moves on to another man in her life. In the meantime, Michael and Laurie attend a period party where Michael tries to stay in the moment, a task to which he is unsuited.

Few readers will like Michael although many will recognize in him some of the men they know. The women in Michael's life, those closest to him -- his wife, his daughter, his girlfriend -- never know what Michael is thinking. Michael compartmentalizes his thoughts, the better to ignore those that arise from emotions. Laurie is trying to figure out Michael's "silences and hard edges," still believes she can, believes Kelly simply didn't know how to love him. Laurie is waiting for "the nothing that is so often there" to "become a nuanced something." The reader gets the sense that Laurie will, in that regard, be following a dead-end path that Kelly has already traveled. To use the phrase that has become so popular, Michael is not "in touch with his emotions." In that regard, Michael is more extreme than most men: he can't seem to express any emotion, no matter how obvious the need for expression becomes.

If this novel has a fault, it is that Michael's inability to say "I love you," even to his daughter, is difficult to believe. By taking Michael to an extreme, however, Robert Olen Butler illustrates a familiar divide between men and women: while Kelly and Laurie are waiting uncomfortably for Michael to say something, to express a feeling, Michael feels connected to them by their mutual silence. There are other moments involving other couples that reveal the different ways in which men and women think and perceive the world, but Kelly and Michael, independently remembering their shared lives, provide the sharpest examples of those differences.

That divide is one of the novel's strongest themes. The nature of manhood is another. We see a bit of Michael's life as a boy, enough to understand that Michael's father conditioned Michael to believe that emotional displays are unmanly. Perhaps it is trite that Kelly's father was emotionally unavailable and that Kelly is likely drawn to Michael for that reason, but sometimes trite is truth: women are often attracted to men who, consciously or not, remind them of their fathers, just as they are often attracted to "the strong silent type" until years of silence become oppressive.

As he explores these themes, Butler constructs sentences and paragraphs that move the narrative along like a locomotive gaining steam. There isn't much of a plot here -- you wouldn't call the events that have shaped your life a "plot" -- although Butler skillfully builds a sense of dread as the story unfolds. Two stories, really, seamlessly joined: one taking place in the present that has the reader worrying about Kelly alone in her hotel room with alcohol and pills, and the intertwined life stories that brought Michael and Kelly to this point. Butler condenses the life stories to their essence by focusing on those small defining moments in lives and relationships that become forever imprinted in memory. I'm not entirely satisfied with the ending -- it seems designed to appease readers -- but that's a small complaint, an authorial choice that I can accept.

The scenes describing the end of the marriage are beautifully written but painful to read. If you're looking for a book that is light and bright and cheery, look somewhere else. If you are willing to tackle an intense, insightful examination of two individuals, this is a rewarding novel.

RECOMMENDED