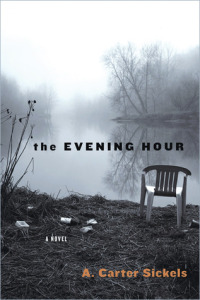

The Evening Hour by A. Carter Sickels

Friday, January 13, 2012 at 6:10AM

Friday, January 13, 2012 at 6:10AM

Published by Bloomsbury USA on January 17, 2012

Cole Freeman grew up with the Bible and little else. Now almost thirty, he’s the only one of his friends who feels no inclination to escape from the mountains of West Virginia -- not by moving or joining the military or using the drugs he sells to supplement his income as a nursing home aide. Cole feels a connection to the land despite the explosions that ravage it as mining companies destroy the mountain tops that surround him. He has no connection to his mother, condemned as a harlot by his grandfather before she walked out of Cole’s life. How will Cole respond when a death in the family brings her back to the mountain?

The strength of The Evening Hour lies in the careful construction of its central character. Cole is a man of unvoiced thoughts, a man who rarely uses more than three words and a grunt to answer a question. He nonetheless has complex feelings: about growing up without a mother; about the serpent-handling, scripture-spouting grandfather who raised him; about his former best friend, Terry Rose, who left the mountain before returning to take a job at Wal-Mart; about the women with whom he has on-and-off relationships; about the government and the mining company and the environmentalists he can’t bring himself to trust. He wants to be a nurse and likely has the aptitude and intelligence to attend college, but can’t muster the belief in himself that he would need to change his life. His grandfather told him many times that he needed to be saved, that he should surrender himself to the Holy Ghost, but salvation eludes him. He understands the appeal of religion but doesn’t have much use for it. He’s frustrated and isolated, confused and tired. He’s nearly thirty but he’s still growing up … or maybe he’s stuck, unable to grow beyond the crabbed, stifling life he’s always known.

Carter Sickels writes vividly of Appalachia: dirt poor people living hardscrabble lives, powerless to contend with the mining companies that poison their water and flood their land; the defiant pride that keeps them rooted in their homes; the lies and threats that mining companies wield to induce landowners to sell their property; their silent fears and fading hopes. The environmental devastation and human suffering inflicted by mountaintop removal (or, more aptly, mountaintop destruction) is movingly depicted. Sickels’ portrayal of the media is insightful: when national news teams arrive to report a catastrophe on the mountain, they focus not on the problem’s cause but on the impoverished state of the mountain’s residents. “See how they do us?” one of the characters asks. “Any time we get attention, it’s to show how backward we are.”

While it is never dull, The Evening Hour is not an action-filled, plot-driven novel. It is the story of one man learning about and coming to terms with his life, a man faced with difficult decisions who is trying to make peace with himself. That’s not to say that the story is uneventful. Cole experiences a life-changing trauma a bit past the novel’s midway point, described in several chilling, unforgettable pages. But the story is more about Cole’s reactions than his actions, more about his thoughts than his deeds. It’s sort of a delayed coming-of-age novel (some people take longer than others to crawl out of adolescence, to make the hard choices demanded by adulthood). Dramatic tension builds as Cole faces a critical decision. His grandfather regarded the mountaintop as proof of God, but the mountain is disappearing. Will Cole share that fate? That question drives the novel, and it kept me engrossed from the first chapter to the last.

RECOMMENDED