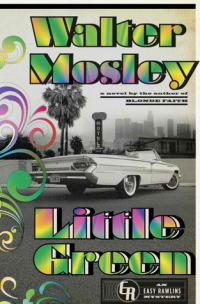

Little Green by Walter Mosley

Wednesday, May 15, 2013 at 11:44PM

Wednesday, May 15, 2013 at 11:44PM

Published by Doubleday on May 14, 2013

The good (if not particularly surprising) news for Easy Rawlins fans is that Easy isn't dead -- he just thinks he is. A few paragraphs into the opening chapter, his revival from a coma gives birth to a new Easy Rawlins adventure. Even before he is back on his feet he has a mission: to find a missing boy named Evander Noon (a/k/a Little Green). At about the novel's midpoint, Easy takes on a second assignment, helping a friend who is the victim of a blackmail scheme.

Walter Mosley always captures the place and time in which his novels are set in high definition detail. Little Green takes place Los Angeles in 1967, a time when hippies were still a phenomenon and the Watts riots were the prism through which whites viewed blacks. Mosley builds characters who, over time, become as familiar and as real as distant friends, yet -- like real people -- they're still capable of surprising behavior. For Easy Rawlins fans, Little Green is worth reading to discover the new stage of his life that Easy has reached. This is a mellower, more optimistic Easy, one who is finally coming to terms with his difficult life, one who, having been reborn, is starting over (just as, in many senses, the country was doing).

It's a given that Mosley's dynamic prose will sweep a reader along from his first word to his last. The plot of Little Green, on the other hand, is less engrossing than Mosley has delivered on his better days. The story moves at a steady pace but it never soars. There are so many backstories in play that they tend to overshadow the central plot. The voodoo medicine that keeps Rawlins going is a silly distraction. Yet Mosley has always been a chronicler of the human condition, and if the plot is unexciting, it nonetheless has revelatory moments that illuminate the darkness within his characters, as well as their struggles to overcome it. Little Green is ultimately a story about a changing world, one that offers more hope than despair. Viewed in that light, the novel is a modest success.

RECOMMENDED